When you’ve been all over the world, and lived in many parts of it, you develop a strong feeling for where you want to call home. So why did Rick Whitworth pick just about the polar opposite of the place where he’d spent his formative years—Texas—trading it for the Pacific Northwest?

“I was thinking about where I wanted to end up and having had the opportunity to live in a lot of places as a result of (a long career in) the Navy, I kept coming back to this place,” Whitworth said. “There are mountains, which I love. There are trees that grow taller than homes, which is unusual in north-central Texas, and the water, which there is an abundance of around here. So, it was a combination of the trees, the topography, the water, and the climate that made me think that this is where I wanted to be.”

Marvin Ultimate windows

Whitworth was introduced to this verdant corner of the U.S. when his ship, the USS Kitty Hawk, was undergoing repairs at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. Storied seaside communities like Port Townsend, with its well-preserved Victorian architecture and boatbuilding legacy, some 42 nautical miles north of Bremerton, caught Whitworth’s eye. From its historic downtown along the water with its shops, art galleries, and restaurants, to its grand captains’ homes and gingerbread detailing, Whitworth was smitten with this “great little town,” as he described it.

Settled on a place to land, Whitworth called a realtor in Port Townsend, who found him his place to build—and it was always a place to build for Whitworth, not an existing home. “I’m a little bit picky,” he said with a grin. “And have definite ideas about architecture.” The spot where his ideas could take shape? Five heavily forested acres on nearby Marrowstone Island.

Getting the Team Together

Left: Peter Bates, Good Homes Construction | Right: Dan Shipley, Shipley Architects

To get the project started, Whitworth needed a team, and his realtor knew just where to turn: Peter Bates, a one-time New Englander who found his way to Washington to attend the renowned Northwest School of Wooden BoatBuilding. Bates had pivoted to home building, and his company, Good Homes Construction, had just completed a house in the Uptown neighborhood of Port Townsend.

“We came to this project in sort of a backdoor in a sense, a little bit of a reverse order,” Bates said. “Oftentimes a project is started, we get contacted by the architect, and the architect will arrange to have interviews with several contractors, and the architect and the owner will select a contractor. In this case, we were approached by a real estate agent who was working with the owner and sold the property.”

Bates’ Uptown project was a modern-style home designed by Dallas-based architect Dan Shipley, which got Bates to thinking: The homeowner, a Texan looking for modern design (Whitworth), and an architect with modern expertise (Shipley), also from the Lone Star State? You can see where this is going.

“We found out that (Whitworth) was living in Dallas, and we had completed a house with a Dallas-based architect, (Shipley), and it was a really great experience. We said, ‘Hey, you need an architect. (Shipley’s) in Dallas. You are in Dallas. This could work out really well,’” Bates recounted.

It also helped that both Bates’ and Shipley’s aesthetic prowess matched Whitworth’s vision. “It was clear that (Whitworth) wanted a special place. He wanted a home that was going to be unique and special and beautiful,” Bates said. “He really liked a contemporary look, and a clean look, and that’s what we do.”

Into the Great Unknown

With the team in place, the project took off in earnest. But from the very beginning the things that gave the project and its setting so much promise—the dense forest, the seclusion, the views—made it uniquely challenging.

“Our initial forays out there were like Lewis and Clark,” Shipley said. “We’re just chopping our way through the jungle, trying to understand what might be out there, where a building site might be. And this was pre-drone times … we came out and did it the old-fashioned way. We took a ladder and stood up against a tree and tried to see where there might be an opening for a house.”

The five-acre site was covered in prickly bramble, and not knee-high shrubbery that a brush mower could take down in a few passes, a six-foot wall of thorny overgrowth tangled among the trees and deadfall. And beyond the bramble toward the western horizon? A 60-foot cliff down to the water’s edge.

“Then we discovered the bluff,” Shipley said. “There’s a very significant bluff that drops off to the water. And we discovered that by coming close to just stepping off.”

For Bates and Shipley, the walking-off-the-bluff crisis was thankfully averted, but as they surveyed what they could of the five acres, the hits kept coming.

“As soon as we walked on the site, we could tell there were wetlands,” Bates said. “We were squishing; our boots were squishing.”

Building atop a swampy ground in a notoriously rainy biome was already a non-starter, and getting it all permitted is another challenge. The pair knew there were going to be seismic issues, wetland issues, and shoreline setback issues. But from constraint comes clarity; in a way these roadblocks helped focus the project. What initially had been a difficult decision of where to put the house on the five acres became an easy one. There was essentially only one build site: a clearing on the western edge of the property, facing the Olympic Mountains and Puget Sound, not far from the bluff.

“It turned out, really, to be in our benefit,” Shipley said, “to work … within the parameters of what the county was going to allow. Restraints often provoke good thinking.”

Good Editing = Good Design

This belief that good editing makes for good design was carried through to the home’s blueprints. Shipley’s first design was too grand; it needed to be tightened up and condensed to fit into the space. The second set of plans was closer, but in his mind, still didn’t truly capture the essence of the property and location.

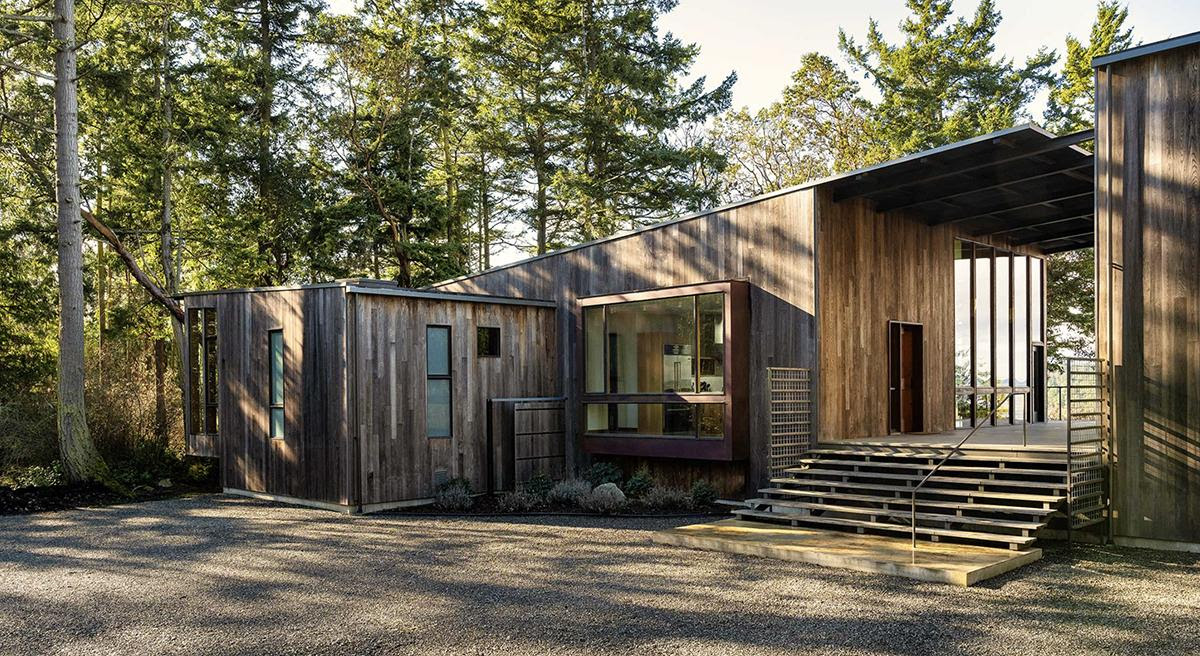

It was the third design that hit the bullseye, and it’s easy to understand Shipley’s vision when you finally see the home, set deep in that impossibly green forest.

“I realized that as you come through the woods approaching the house, you don’t know what you’re going to arrive at. You have no idea,” Shipley explained. “You’re just arriving at this bluff and this vast western sky and a view of the Olympic Mountains. That’s what led to this version of the plan, where we have this big connecting outdoor space.”

The main house is really two structures, almost like a Fabergé egg laid on its side and pulled apart, tied together by a surrounding deck some five feet off the ground (to raise the buildings’ profile above the waves of tall vegetation). The space between the two buildings is what creates that unimpeded western view as you arrive at the home, just as Shipley had hoped. It’s this framed space, the “dog trot,” that visitors can’t stop talking about.

“It’s what we call a ‘dog trot,’ based on an old Southern kind of plan,” Shipley said. “Where they would build two separate houses with a common roof and that space in-between.”

What differentiates this PNW dog trot from its Southern counterpart is another ingenious sleight of hand: The roof does not extend all the way across between the two buildings. What’s lost in Washington State rain protection with this design is more than made up for by an even more precious commodity: southern sunlight.

“We wanted to connect visually the two spaces: the interior of the main living space and the dog trot,” Shipley explained. “So we made the tallest windows in the house face that way because we wanted to connect the house to the sky right through there. And the sun, coming down through that gap and providing these shadows and the beams throughout the day, they’re a little bit like a sundial. You can see how the day is progressing based on where the shadows are.”

Where Windows Meet Boatbuilding

Those main living-space windows, 12-foot Marvin Ultimate Direct Glaze windows situated atop 3-foot units, are a sight to behold from inside the house. Trimmed entirely in show-stopping Douglas Fir, they’re warm, soothing, and provide an inviting radiance—often in contrast to the gray-green surroundings outside.

“We wanted the house to feel very warm, and particularly through the winter months when it’s cold, cloudy, and rainy,” Shipley said.

Rainy days or sunny ones, it only seemed right that the maritime histories of both Bates and Whitworth made their way into the final designs and material choices of the project. Shipley was more than happy to oblige.

“We wanted the house to really take on the qualities of a vessel, more like a boat, really,” Shipley said. “And with a boat, the interiors are typically wood. And so, we followed that model here, where the floor just wraps up onto the walls and fills the spaces between the windows.”

Bates’ boatbuilding experience came in handy all throughout the project, from sourcing reclaimed wood from a shipyard for the kitchen partition to putting the house itself together—and especially installing the floors and windows. With the straight-grain Douglas Fir flooring running right up to the Marvin Ultimate windows, attention to fit and finish was imperative.

“On a house like this, a really modern house, there’s not a lot of trim. We don’t have crown mouldings. We don’t have really wide window and door trim. We don’t have tall baseboards. We have almost no trim in a house like this,” Bates said.

“To try and get those lines to be clean, and without being able to cover things up with trim, it takes a huge amount of work … you need to take care of all that in your framing because there’s just no wiggle room. There’s no escape hatch, or being able to just put trim over it.”

In a completely bespoke project like this, Bates felt especially supported by Marvin: “The Marvin Ultimate line was great because they are so customizable, and you can talk to the factory, and you can talk to the reps, and they’ll work with you to say, ‘What are you trying to accomplish? How can we do this? Is that window too big? Will this work this way?’ That was a real appeal of the Ultimate line is how customizable it is.”

Views in all Directions

Views in All Directions“Floating amongst the tree trunks” is a perfect way to describe the entirety of the Marrowstone Island project. Stand on the deck and in one direction you can see all the way to Port Townsend, its ferry making round trips across the water. Slowly turn, and behind you’ll see two trees framed by the “dog trot,” standing sentry over the forest-darkened driveway; trees that were themselves guarded for a time by plywood sheeting during the build to help protect them from an overzealous delivery driver or construction truck. From that spot on the deck, it’s most apparent: the house is the result of a shared vision come to life in the woods, perched first above a sea of grasses, and then farther out, high above Puget Sound.

Views in all Directions

While the living room, with its expansive windows and Marvin Ultimate Sliding door, takes full advantage of the views and fresh air afforded to the project, it’s the primary bedroom where Bates’ floor-to-ceiling window exactitude met its truest test, and best expression.

Cantilevered out from the house, and boasting picture windows that touch the floor and ceiling on three sides, the room is like the most refined treehouse you’ll ever see.

“We tried to make it all about this small space in the trees, almost like you’re camping out, having a mattress in the trees,” Shipley said. “You have that sense of just floating amongst the tree trunks.”

If you are interested in learning more about Marvin, please call (510) 649-4400 or text us at (510) 841-0511 and speak to our window and door experts.

Join our mailing list, follow us on social media, check out our events page on our home page of the website to feed your design curiosity, find solutions and stay inspired.

Please schedule an appointment here to view our vast selection of Marvin windows and doors.